From our content

Student years and studies

Dear reader! Here you can read about how an average student became a doctoral student at Cambridge University. We look at Albert Szent-Györgyi’s student years, which the First World War and love played a huge role.

Szeged and the Nobel Prize

This section summarises Albert Szent-Györgyi’s years in Szeged and the events surrounding his Nobel Prize.

The World War and beyond

In this section, you can read about how the now Nobel Prize-winning scientist survived World War II and why he was eventually forced to settle in the United States. This section looks at the last phase of his life.

The World War and beyond

In 1939, the Second World War broke out and Szent-Györgyi was again confronted with the human cruelty he had experienced during the First World War; but he could not stand by and watch.

„I did not go into politics. Politics entered our lives, when books were burned and my Jewish friends were persecuted, I had to say yes or no. And I said no.”

Albert Szent-Györgyi

(Moss, 2003, 148.)

The spy story

Szent-Györgyi joined the Hungarian National Independence Front, which was organised by intellectuals. He also participated in writing their famous manifesto that urged politicians to withdraw Hungary from the war, recall the remaining Hungarian troops and break off any relations with Germany. In domestic politics, they demanded freedom of speech, improvements for the working class and secret elections. Of course, the government did not comply with all this, as it would have led to an open war with Germany.

However, the courageous stand of Szent-Györgyi was noticed by István Bethlen, former Prime Minister, who sought a way out of the war and called for signing a separate peace. Bethlen was well aware that the British trusted the scientist, who had lived and worked in Cambridge for many years. That is why he asked him to go to a conference in neutral Turkey to meet the members of the British secret service and try to initiate peace negotiations. With this plan, Szent-Györgyi approached the then Prime Minister of Hungary, Miklós Kállay. This is how he wrote about it later:

„I told him about my plans to go to Istanbul. Kállay was apparently a Nazi, but I suspected that he was in fact a good Hungarian, and he was just waiting for the chance to take his country to the other side. My hunch was correct. Instead of ordering my arrest, he asked me to represent him and to deliver certain messages to the Allies.” (Moss, 2003, 148.)

„Istanbul was the world centre of espionage at the time, I felt like a lost sheep there, but eventually I managed to get in touch with the British secret service. I was ordered by the British Admiral to go back to Hungary, set up a secret radio station and transmit information between the British and Hungarian governments. So that’s what I did, I went back, I started to organise the station, but they figured out my plan, and I was arrested. But I managed to escape. Hitler was screaming my name in rage, at the top of his lungs. He ordered the Hungarian governor to visit him and demanded my transport to Germany to show the world how to deal with a ‘Schweinehund’ (pig dog). After Hitler invaded Hungary, the entire Gestapo (the German military secret service) was on my tail, so I had to hide as carefully as possible to continue my anti-Hitler underground activities. […] In these very difficult days, the Swedes helped me with a great offer. To enable the Swedish ambassador to help me, I was made a citizen by the King of Sweden. I even got a new name: I was Mr. Swenson, my wife Mrs. Swenson. Without the help of the Swedes I would not have survived the war, but even with that help I needed a lot of luck to stay alive.”

Albert Szent-Györgyi

(Moss, 2003, 151.)

...

After the war

Szent-Györgyi had to hide for two years while the Germans tried to capture him. Finally, in 1945, the Soviet army occupied Budapest and drove out the German invaders.

„After the Soviet army occupied Budapest, a special military unit was sent to Hungary on Molotov’s personal orders to take me to safety. They successfully found me and fed me at the Soviet army headquarters. I was then taken to Moscow, where I was treated as a high dignitary and given caviar three times a day.”

Albert Szent-Györgyi

(Szent-Györgyi, 2017, 26.)

dignitary:

senior official, high-ranking person

♦Hover your mouse over the book!♦

When he returned from Moscow after the war, he found the country in ruins. He tried to rebuild Hungary’s cultural life. To do this, he realised that we would have to maintain good relations with the occupying Russians. While working on some sort of consolidation between Hungary and Russia, he took another extremely important step: to rescue the most outstanding Hungarian intellectuals, he established the new Hungarian Academy of Sciences on 6 September 1945. The following year he himself became the President of the new Academy of Natural Sciences.

Also in 1945, he was appointed head of the Institute of Medical Chemistry at the university of Budapest.

He also threw himself into politics with enthusiasm and the hope for peace and freedom. However, he soon had to realise that the „Stalinist peace” implemented by the Russians did not result in the democratic state the country had longed for. At the same time, one of his greatest fears seemed to be confirmed: he was becoming increasingly isolated from Western European academic life, and even contact (i.e. correspondence) with the Western academic circles was difficult.

The idea of emigration had not yet occurred to him, but he longed to go abroad, mainly to advance his research.

The final decision to start a new life abroad came after the arrest and torture of a friend in 1947. István Ráth was a wealthy businessman who, after the war, supported Szent-Györgyi in founding the new Academy and provided financial support for his laboratory research. As the divide between capitalism and communism grew in the country, Ráth, a wealthy industrialist, became undesirable. When Szent-Györgyi heard that his old friend and supporter had been imprisoned, he used all of his political influence to free him. Ráth was eventually released, but he was tortured to the point where he could not stand for two weeks.

In July 1947, Albert Szent-Györgyi, along with his second wife, Márta Borbíró, her parents, and István Ráth applied for admission to the United States.

The US, however, did not seem to welcome the suspected communist scientist with open arms, as his visa application was repeatedly rejected. Finally, with the help of his former research partners, he got permission from the Attorney General (Tom Clark) to settle in the United States, and soon found a job as the Director of the Muscle Research Institute at the Marine Biological Research Laboratory in Woods Hole.

He lived there for almost forty years, from 1947 until his death in 1986.

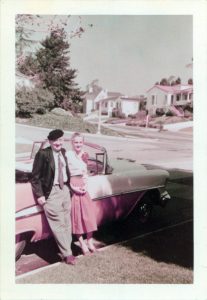

The professor seemed to have finally found peace and tranquillity in America, and freedom and support for his research. Many friends and acquaintances visited their home in Woods Hole, known as the „Seven Winds”, and there was always a lively social life.

After the death of his wife, Márta Borbíró, and his daughter Nelli, Szent-Györgyi turned to cancer research. He first wanted to understand the nature of the disease, because he believed that this was the only way to find a cure. He defined the theory of how cancer develops and tried to cure the disease with plant-based substances (mainly wheat germ). In the last decades of his life, he devoted himself to cancer research.

He got married two more times in America, but his third marriage failed and was short-lived. He and his fourth wife, Marcia Huston, remained together until the professor’s death.

After his emigration, he visited his homeland for the first time in 1973, when he was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Medical University of Szeged, and in 1978 he visited the country as a member of the delegation that brought the Hungarian Holy Crown home.

He died on 22 October 1986 in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, at the age of 93.

Previous chapter

Szeged and the Nobel Prize