From our content

Student years and studies

Dear reader! Here you can read about how an average student became a doctoral student at Cambridge University. We look at Albert Szent-Györgyi’s student years, which the First World War and love played a huge role.

Szeged and the Nobel Prize

This section summarises Albert Szent-Györgyi’s years in Szeged and the events surrounding his Nobel Prize.

The World War and beyond

In this section, you can read about how the now Nobel Prize-winning scientist survived World War II and why he was eventually forced to settle in the United States. This section looks at the last phase of his life.

Student years and studies

Albert Szent-Györgyi was born in Budapest on the 16th of September 1893. His mother was Josefina Lenhossék, his father was Miklós Szent-Györgyi. Albert was most influenced by his mother and her family, as he lived with her and his brothers, as well as his maternal grandmother and uncle in Budapest, while his father was mostly at the family’s countryside estate.

He went to the Budapesti Református Főgimnázium and was not a good student at first. By his own admission, it was only in high school that he decided he wanted to be a scientist. Until then he was a mediocre student, not really knowing what he was really interested in. He later recalled:

„I must have been a very slow-witted young person who only started to develop after adolescence, and as a result I was considered a backward child in the family. So when I announced my intention to become a scientist at the age of sixteen, I met with fierce resistance.”

Albert Szent-Györgyi

(Szent-Györgyi, 2017, 15.)

But his high school diploma was excellent so the family agreed that it was worth sending him to university.

boring medical practice

getting familiar with laboratory research

New grounds: studying living organisms

mandatory military service on the war front

In 1917 he received the diploma he had obtained at the Faculty of Medicine of the Royal Hungarian University of Science in Budapest

Married Kornélia Demény

He reported his superiors for experiments on Italian prisoners of war for which he was punished

Bratislava, Prague, Berlin, Hamburg, Leiden and Gröningen

1911-1918: University - the war intervenes

Szent-Györgyi enrolled at the Medical University of Budapest, but it soon became clear to him that he was not interested in boring medical practice, but rather in the laboratory practice and research. At that time, however, there was no research training in Hungary, and even biology could only be studied at the university of medicine, which is why Szent-Györgyi applied to study there.

So, very soon, he ended up in the anatomy laboratory of his maternal uncle, Mihály Lenhossék. He learned the basics of laboratory research there, and he became familiar with the important laboratory instruments and chemicals essential for experiments. At the age of 20, as a third-year university student, he was already publishing articles in German.

Soon, however, the First World War broke out, in which Szent-Györgyi also served in the military. This is how he describes this period.

„By the third year of the war, I could see clearly that we were losing, and sacrificing ourselves senselessly for the sake of a few high-ranking war criminals. I was deeply disgusted with military life and did not find it glorious to go down as a hero in battle. I believed I could do more for my country if I stayed alive. But I also felt a burning desire to return to science. So one day in Poland, on the Russian front, I grabbed my rifle and shot through my left upper arm.”

Szent-Györgyi, 2017, 18.

Szent-Györgyi was sent home to Budapest, where his wound healed quickly, so he was able to complete his university studies and receive his medical degree from the Faculty of Medicine of the Royal Hungarian University of Science in Budapest in June 1917.

After graduation, he married the beautiful daughter of the chief executive officer of the Hungarian Royal Post Office, Kornélia Demény.

In 1918 he was stationed in a laboratory in Italy. There, he could not stand by and watch his superiors carry out cruel medical experiments on Italian prisoners of war, so he reported them. The military leaders, as punishment for his recklessness, transferred him to a malaria-infected area, but fortunately he never arrived there. This was due to the fact that, in the meantime, his daughter, „little Nelli”, had been born, and by the time he returned from his due leave, the Great War had just ended.

„I only stayed there for a short time, since in the hospital, which the laboratory was part of, a Viennese doctor was conducting dangerous experiments on Italian prisoners, saying they were ‘just’ prisoners. Brotherly compassion for my fellow human beings overcame me, and I was so outraged that I reported the incident to the army. The doctor had two stars more than me, so they had to punish me. I was sent to the swamps of northern Italy where life expectancy was very short due to tropical malaria. Fortunately, after a few weeks the war ended and I was able to go home.”

Albert Szent-Györgyi

(Szent-Györgyi, 2017, 18.)

1919-1931

Between 1919 and 1926 he worked in many places, including as a medical researcher in Bratislava, Prague, Berlin, Hamburg, Leiden and Gröningen in the Netherlands.

In 1926, he attended a congress of the International Union of Physiological Sciences in Stockholm, where the opening address was given by one of the eminent authorities of the time, the biochemist Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins. He repeatedly mentioned the then unknown name of Szent-Györgyi and later invited him to Cambridge. Szent-Györgyi considered this university town to be his „scientific homeland”.

He received his doctorate here in 1927 for his work on the isolation of ascorbic acid.

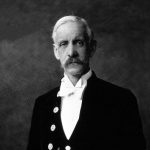

Sir Frederick Gowland Hopkins

English biochemist

member of the Royal Society

awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology

„I originally called ascorbic acid „ignose”, because I didn’t know exactly what it was (ignosco means I don’t know). Harden, the editor of the Biochemistry Journal, scolded me for making fun of science. My „Godnose” suggestion was no more successful. Finally, after it was shown to be identical to vitamin C, Professor Haworth and I named it ascorbic acid.”

Albert Szent-Györgyi

(Szent-Györgyi, 2017, 22.)

He worked for a year in the United States of America at the Mayo Foundation in Rochester. Here, he succeeded in producing ascorbic acid (then called hexuronic acid) from bovine adrenal cortex.

But how did Szent-Györgyi know where he should look for the mysterious compound?

He observed that certain vegetables and fruits turn brown after being damaged (e.g. apples, potatoes, bananas). He linked this to his knowledge that the skin of patients with a condition called Addison’s disease turns brown. This condition caused by adrenal insufficiency. This is how the professor realised that the adrenal gland could be the oxidation centre of the human body.

Although this theory has since been shown to be false, it set Szent-Györgyi on the path to his research on biological oxidation.

Next chapter

Szeged and the Nobel Prize